The scene opens with a camouflage-coloured plane, crashed and smouldering off to one side, and a rusty car jutting into the grass on another. Between them is a giant sign that says “I ❤️ SAGAR”. As the dramatic background music swells, Rohitash Yadav and his friends drop into the video frame, which is overlaid with stats and menus. The characters dance, imitating animated figures. Rohitash wields a skillet as a weapon.

The video is PlayerUnknown: Bundeli Ground, a “Real Life” battle on Rohitash Yadav’s YouTube comedy and spoof channel. Shot around Sagar, Madhya Pradesh a couple of months ago, it fuses Bundeli dialogue with the scenes, memes and animated effects of the smash-hit multiplayer game PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds, otherwise known as PUBG. As Rohitash’s squad assembles, one of the characters proposes his plan. “I was thinking. Let’s go to Surkhi. We’ll eat some bada and kill some people. Three-four of them.” Surkhi, a town about 30 kilometres from Sagar, is famous for its mangodi (or bada). And killing people, as at least 50 million Indians know, is the primary aim of PUBG.

From Rohitash Yadav channel’s PlayerUnknown Bundeli Ground.

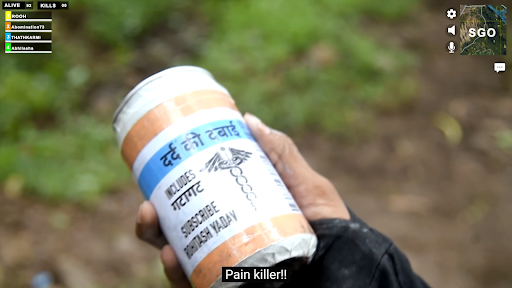

The four players (three guys and a gal, plus extras) attempt to do just this, crawling between fields, past a man urinating in the open, in and out of rickety jeeps and ruined buildings. Bundeli Ground is interspersed with plugs for local businesses – presumably sponsors – such as the Hinduja Supermarket App, and City Diary, a Sagar-based directory app. At one point, an actor finds a can of “dawa” or medicine on a rock; its label includes a reminder to subscribe to Rohitash’s channel and a mention of the ingredient gatagat, an ayurvedic digestive mixture.

Bundeli Ground was released on August 25, just over a week before the Indian government banned PUBG Mobile and its Lite version, along with over a hundred other apps that were engaged in activities “prejudicial to sovereignty and integrity of India, defence of India, security of state and public order.” The decision, the government declared, was “a targeted move to ensure safety, security and sovereignty of Indian cyberspace.” The ban followed increased border tensions with China (a Chinese company co-produced PUBG Mobile) and came on the heels of a late-June ban on 59 other Chinese apps, most notably TikTok.

The players of Bundeli Ground never got to their “Chicken Dinner” – part two of the video, slated to come out in September, hadn’t been released at the time of publication. But YouTube is a loot box of similar videos from all over the country. From just around Bundelkhand there’s one featuring kids with sticks for weapons; another with props like tawas, saws and motorcycle helmets; and one that ends with the game buddies enjoying a “Paneer Dinner” after realising that it’s a meatless Tuesday. As they polish off their literal paneer, the players raise a toast: “Jai PUBG, Jai Bundelkhand!” Could anything be more Indian?

Screenshots from PlayerUnknown Bundeli Ground on Rohitash Yadav’s YouTube channel.

PUBG Mobile launched worldwide in March 2018, quickly going viral. Until the ban, India had the biggest share (24 percent) of worldwide downloads. Some 2.5 lakh students registered for a Campus Championship later that year. After PUBG Mobile Lite came out in July 2019, along with a Hindi language option, the game became even more deeply entrenched in Indian youth culture. According to Google Trends, over the last year, the highest interest in PUBG came from smaller cities. As Khabar Lahariya journalists reported in the towns and villages of UP and MP through the lockdown, they noticed more and more kids and teens (particularly boys and young men) glued to the game.

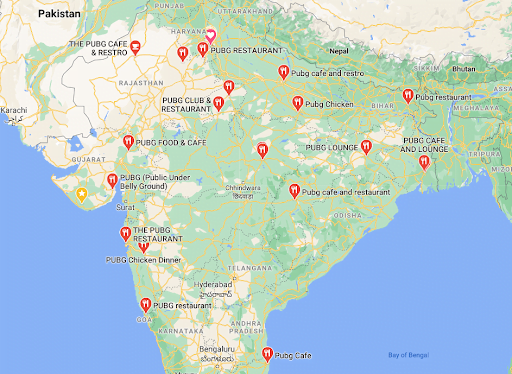

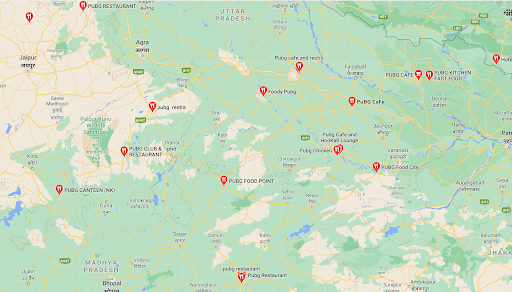

The trend in Bundelkhand was part of a national craze, as PUBG-themed restaurants and cafes sprouted up across the country. And of course, there were PUBG pre-wedding photo shoots and YouTube albums. In a couple of cases, PUBG even invaded marriage ceremonies, with pictures of grooms more engrossed in a game than in their brides going viral. Mainstream media coverage mostly focussed on the app as this uninvited party guest, warning people first about its addictive influence, and then more recently about its potential as a Chinese spy app. But although the platform may be part-Chinese owned (this is changing after the ban), the content – just like gobhi Manchurian – is completely Indianised.

Double regrets if any of these PUBG-themed venues are also Chinese restaurants.

BREAKING NEW GROUND

After the ban was announced, India’s top PUBG Mobile players – some of whom actually earn a living off of prize money, YouTube channel memberships and other PUBG-related revenue streams – rallied behind the government. Top-seeded player Naman Mathur, aka SouL MortaL, who earlier helped promote the 2019 film Uri: The Surgical Strike in a game with actor Vicky Kaushal, held a YouTube livestream titled “Lets Calm down and talk”. As he streamed, fans asked questions, suggested playing PUBG via VPN, and donated small amounts of money, from Rs. 40 to Rs. 2,000. Since the ban, SouL MortaL has broadcasted his gameplay of other streaming games, like Free Fire and Valorant. Among his suggestions during the Q&A was holding a FIFA Xbox tournament.

But for PUBG’s growing small-town and rural user base, who managed to load PUBG Mobile Lite over connections that are too glitchy for online classrooms, Xbox or PC-version tournaments aren’t really an accessible option. Shortly after the ban, KL reporters spoke to kids and young adults in Chitrakoot and Ayodhya districts. Some, like sisters Pragya and Pratibha Tiwari, were mostly pleased, even though they admitted PUBG was a “good game.” Said Pragya, through her giggles, “My brother played too much PUBG and his studies were suffering. If he saw it on anyone’s mobile he immediately had to start a game. People got too wrapped up in it, so it’s a good thing that the Modi government has banned these apps from China.” Her friend Dinkar Jaiswal piped up, “People were losing their minds over PUBG. And the Chinese used it to steal data, that’s why it’s banned.”

Slightly older players, like Moin, who works in a shop in Chitrakoot, were disappointed, but mostly sanguine, perhaps hoping that the ban would be reversed eventually. Moin had been playing for about six months. “At first, I’d play all night. I’d go to sleep only when it was getting to be morning,” he said. At the time of the ban, he was only playing a couple of hours a night. “It was a good way to unwind after work,” he said. “You can play anywhere, anytime. And time flies – you can play for two hours and it feels like just half an hour has passed.” For Moin, the game was “timepass”, but he sympathised with people “who had put a lot of money into this. I heard of someone putting eight or nine lakhs into buying skins. They’re the worst affected. And YouTubers who were running their households off the money they’d earn from streaming PUBG videos non-stop.” As he pointed out, some of these players had gone pro, and were now facing an uncertain future.

“There’s no better game – nothing will ever feel the same.” – Ajay Kushwaha

Moin doubted that another game could replace PUBG for him, a sentiment we heard again from Ajay Kushwaha, the one interviewee who very openly opposed the ban. Ajay, who works at his uncle’s tea and snack shop in Chitrakoot, said he used to play Free Fire, but downloaded PUBG around May at the insistence of his friends. “As soon as I downloaded it, they started pushing me to buy a royale pass. They said, it’s never going to be shut down, keep playing bro, it’s fun.” Ajay purchased the pass for Rs. 900 and was upset that he now couldn’t use it. “I used to play from midnight to 3am,” he told us. “And sometimes in the mornings if the bazaar and shop were shut. My uncle would yell at me, my family – everyone says it’s useless.” He was bereft at the ban. “There’s no better game than this one… nothing will ever feel the same,” he said.

There were a few reasons for why PUBG had become so beloved. For Moin, the multiplayer game offered a chance to meet new people because of its team format. “There were a lot of people – unknown people – we’d end up talking to them, having conversations. We’d become friends and exchange numbers, too. You could make new friends from anywhere.”

“It’s fun because your voice comes through,” another player, Faiz, told us in May, when we reported on the PUBG craze in Chitrakoot. Besides the incentives of “coupons, achievements, food, guns and skins,” Faiz said “the game is more amazing because your voice goes online and you chat while playing.” Another Chitrakoot PUBG enthusiast, Raj, mentioned the referral code system was also motivational – for each referral you and the new player got Rs. 10. “I refer my friends – from Whatsapp groups, Facebook groups, Telegram channels.” PUBG opened up the way Raj used other apps, like Telegram, which saw a 65 percent increase in Indian users in 2019. “Telegram it’s better because there you can find all kinds of people, from everywhere,” Raj said, hinting at the opportunities for national and international exposure that platforms like PUBG provided for young people who can feel stuck with widespread unemployment and lack of development.

Sandeep Kumar in Ayodhya district said, “There are lots of mobile games, but PUBG was something else. You could travel anywhere to play – by car, by helicopter, jetski. And communicate with others.” Ajay Kushwaha too said that PUBG allowed him to “go somewhere else in my head, where I feel better, different.” He gestured around the shop, “The thing is, I’m always busy with something or other. Without PUBG to look forward to, what’s the point of this dukaandari?”

We found fewer women playing PUBG, but those who did enjoyed it for similar reasons. Sana, in Chitrakoot, had just started playing when we spoke to her in May. “My brother keeps playing, so that’s how I started,” she said. “I have to finish all my work at home and then I play for around two hours – and then maybe play something like Ludo. My mother isn’t happy about it, but I don’t play in front of her.”

THE TROUBLE WITH TIKTOK

On the whole, the “PUBG premis” we spoke to after the ban weren’t too shaken by the news. PUBG has had its fair share of controversies since it launched in India (and elsewhere; it was famously banned in China for being too violent and re-released as Game for Peace). Perhaps people have become somewhat inured to sudden government orders and later reversals, or perhaps the pressure to conform to patriotism is too strong. Looking back to the TikTok ban in May – before the wildly popular video editing and sharing app was briefly unbanned, then banned for good a month later – people were more outspoken against the government’s decision.

“Bad people can make videos, but the videos themselves are not bad.” – Saumya

KL reporters asked TikTok users around Bundelkhand for their reactions. “It’s really upsetting,” said Saumya, a student in Chhatarpur district. “A lot of people earned money from this and their rozi-roti is finished. And kids enjoyed it. TikTok isn’t a bad thing. Bad people can make videos but the videos themselves are not bad.” Her friend Kirti added, “Obviously if you use it too much, that’s a problem, but if you use it properly, it’s good.” Still others, like Saurabh, a 19-year-old in Mahoba, were in denial. “It’s fake news,” he said. “It’s just been removed from the App store. We’ll keep making videos. It can’t shut down.” We found just one dissenting opinion from the slightly older Balu Khan in Chhatarpur, who called the content “rubbish videos” and said TikTok was “ruining the lives of children and youth.”

But by June and the second ban, the discussion had shifted from banning TikTok on moral grounds towards a patriotic defense of the move. Divakar Kumar, a TikTok user from Jana Bazaar, Ayodhya said the danger from Chinese hackers was too great a risk. “Yes people have suffered, but the nation has benefited, no?” he said. His sentiments echoed what we’d been hearing through the month, and saw reflected in the call for a China boycott. In mid-June, an activist group burned the Chinese flag and an effigy of Xi Jinping at Mahoba’s Alha Chowk.

The mobile shopkeepers we spoke with were defensively patriotic, reluctant to speak about the boycott, and when pushed, resigned about the boycott of Chinese goods. “Around 20 percent of people prefer made-in-China smartphones because of quality reasons,” said Arvind Kumar Shivhare, a shopkeeper in Mahoba. “If I can give a made-in-India phone I try to do so.”

Mayank, another mobile shop owner in Mahoba was more cagey. “There’s no damage to me,” he said at first. “People do ask for Chinese products. I’ll sell what’s in stock and then I’m not supposed to sell, right? Because India’s wealth should stay in India, right?” He sounded unsure of his own argument, his reply coming out like a question. After a bit more probing, Mayank said he was considering opening a clothing shop, though the mobile business had been a more profitable concern in the past. “Businesses is maybe 50 percent affected,” he admitted. “Whatever Indian products come out, I’ll sell those… it’s not going to happen soon,” he mused. He still had around five lakh rupees worth of Chinese products in stock.

And Arvind Kumar, despite also having unsold Chinese inventory, eventually dismissed our questions with an appeal to national pride. “It’s fine,” he said. “If our country feels it is important to ban Chinese products, then it’s important. This isn’t my idea, it’s the will of the country’s 30 crore people. If there’s a fight and a push at the border, then the people must come together to boycott Chinese products. Whether it’s mobiles or the LEDs and other things we use in festivals.” Then he added pragmatically, “There are also lots of phones and products coming from places like South Korea and Japan. We’ll sell items made in Vietnam, America, too besides India.”

Rohitash Yadav’s channel actually captured this attitude perfectly in a video where a beleaguered shopkeeper tries to persuade a customer (who wants to play PUBG and make TikTok videos) to just buy the Chinese phone he is recommending. The video is cheeky (“Boycott? What boy cut? I’ve been growing my hair for months now!”) and knowing, but it still ends with a hand-on-heart hashtag check for #vocalforlocal.

MAKE IN INDIA

“There should be a launch [of TikTok], but an Indian launch,” Divakar Kumar from Jana Bazaar declared; and indeed Indian versions of TikTok, PUBG and other apps are already available or in the pipeline. But even as people speculate about the launch of FAU-G, the track record of Indian apps – not to mention government-backed “smart” solutions from healthcare, to education – is less than stellar in India’s less developed regions, despite the title of this KL series.

The TikTok makers we spoke with in June were trying to put a brave face on the prospect of a future without the app. Pratibha Tiwari, who used to make TikToks with her sister, some of which she’s put on YouTube, pointed out, “See, TikTok has been banned, but people’s talent has not! If you put in the hard work you were doing on TikTok on YouTube…” She added, “There’s Roposo as well, but it’s not that great. I checked it out – there weren’t that as many filters as in TikTok. TikTok was a very good app for becoming famous, for making your future.” She quickly qualified this – “But it was Chinese, so it’s good that it’s been banned.”

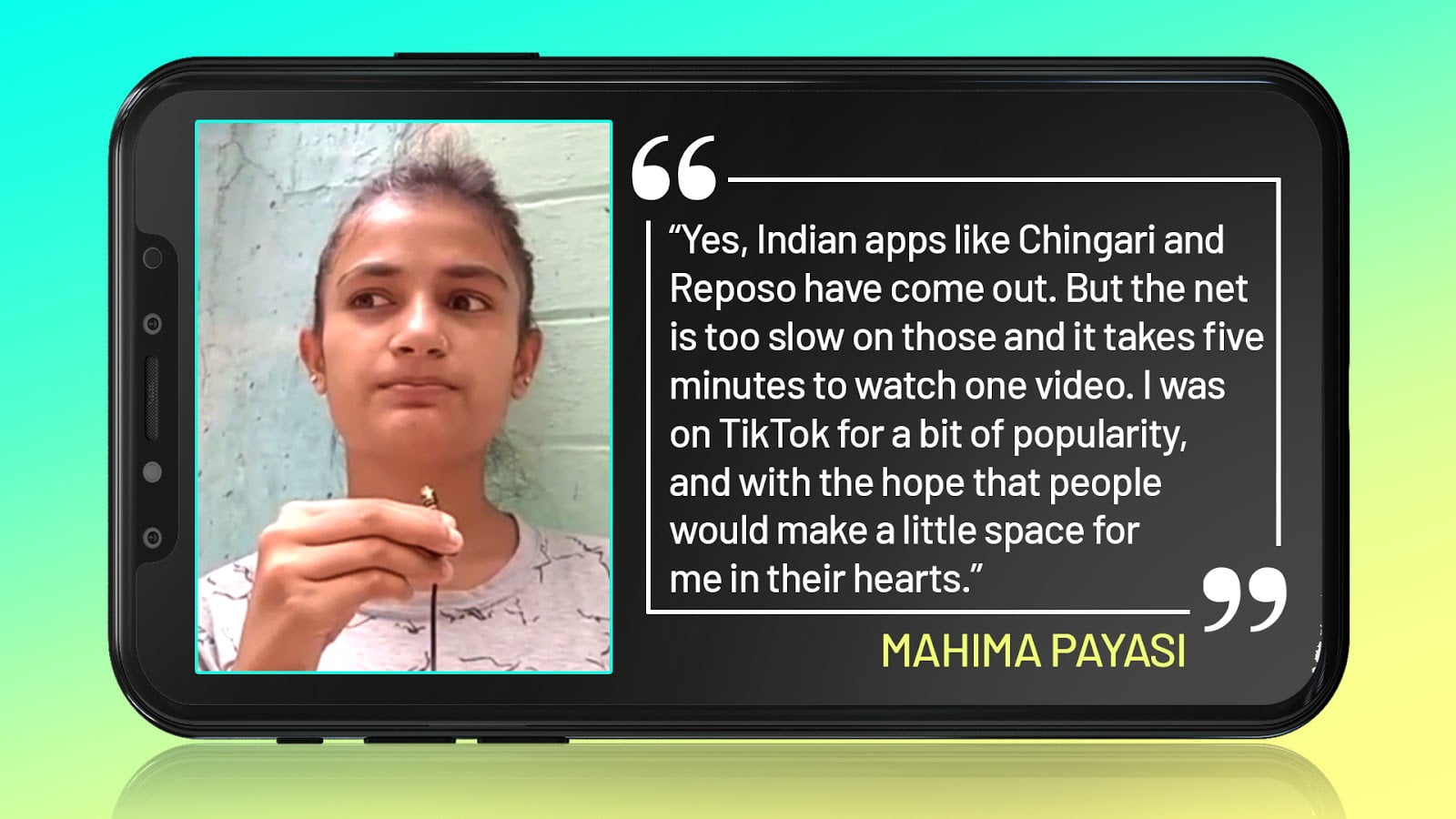

Mahima Payasi, a rising TikTok comedian from Chitrakoot who had over 2.2 lakh followers before the ban, didn’t mince words about Indian apps. “Yes, Indian apps like Chingari and Reposo have come out,” she said. “But they don’t work so well because the internet is too slow. They’re for short 15-second videos like TikTok, but TikTok was something else. The data used to work well on it, but when I tried Roposo it worked very haltingly. It takes five minutes to watch one video.” Mahima had put up some content on Instagram and YouTube, but her small followings on these accounts are far from her dream of “completing one million followers.” Mahima told us, “I wanted to be a bit popular. I hoped people would make a little space for me in their hearts too. That’s it.”

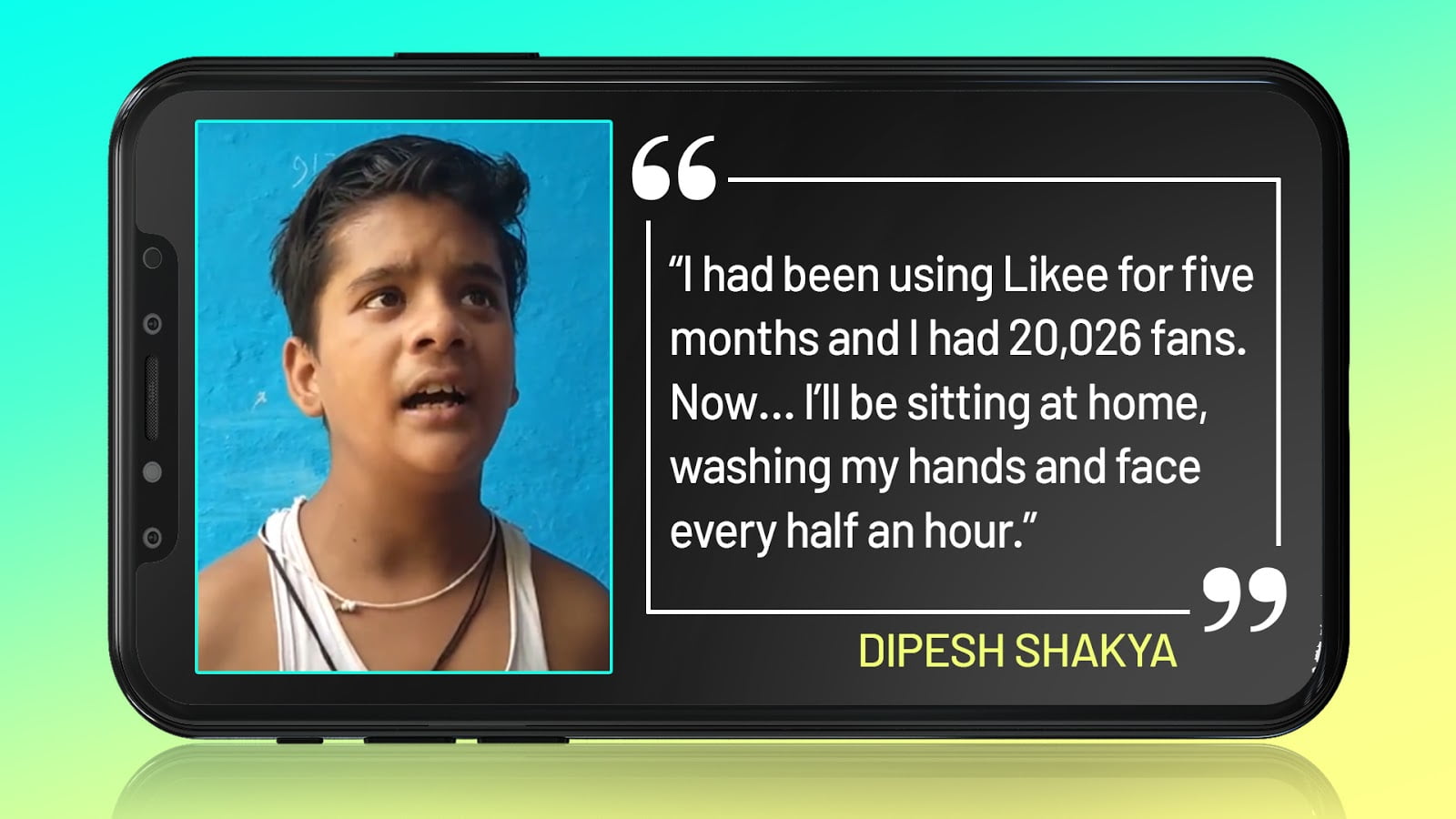

Dipesh Shakya, from Panna district had “20,026 fans” on Likee, another banned app, after five months. “I even asked my brother for a new mobile and got one after a lot of hard work. Then TikTok was banned, then Likee. Now they’re saying even the guy who makes food – manchurian vanchurian and all – should all be banned.” Young Dipesh was cynical about the future. “Now, I guess I’ll be sitting at home, washing my hands and face every half hour.”

Devoid of trending Indian accounts, the landscape of TikTok looks strangely manicured. The app put relatively slick and easy-to-use editing tools in the hands of Indians who, as Slate argued, were given a platform and “validation” for the first time. The writer, Nitish Pahwa, observed that in “a highly stratified society, a video app with a notoriously addictive algorithm happened to cut across castes, faiths, and other gulfs, all so Indians could watch one another’s lip-syncs and skits.” Pratibha Tiwari, who is getting a diploma in mechanical engineering, told us that “People at home, especially our father, really don’t like us to make TikToks. They think we should be focussed on studying. But for one’s own motivation, a person can’t study all the time. They need to be able to enjoy themselves too.” There were certainly issues, but when TikTok was banned, many Indians lost a form of democratic entertainment, and a platform where that elusive commodity “talent” ruled alongside local humour. In the world of TikTok, talent was more important than privilege or international exposure, even if it could clear a path towards them.

He wears the pants and wields the pan. Gender roles reversed in this PUBG pre-wedding photoshoot, complete with screen glitch effects.

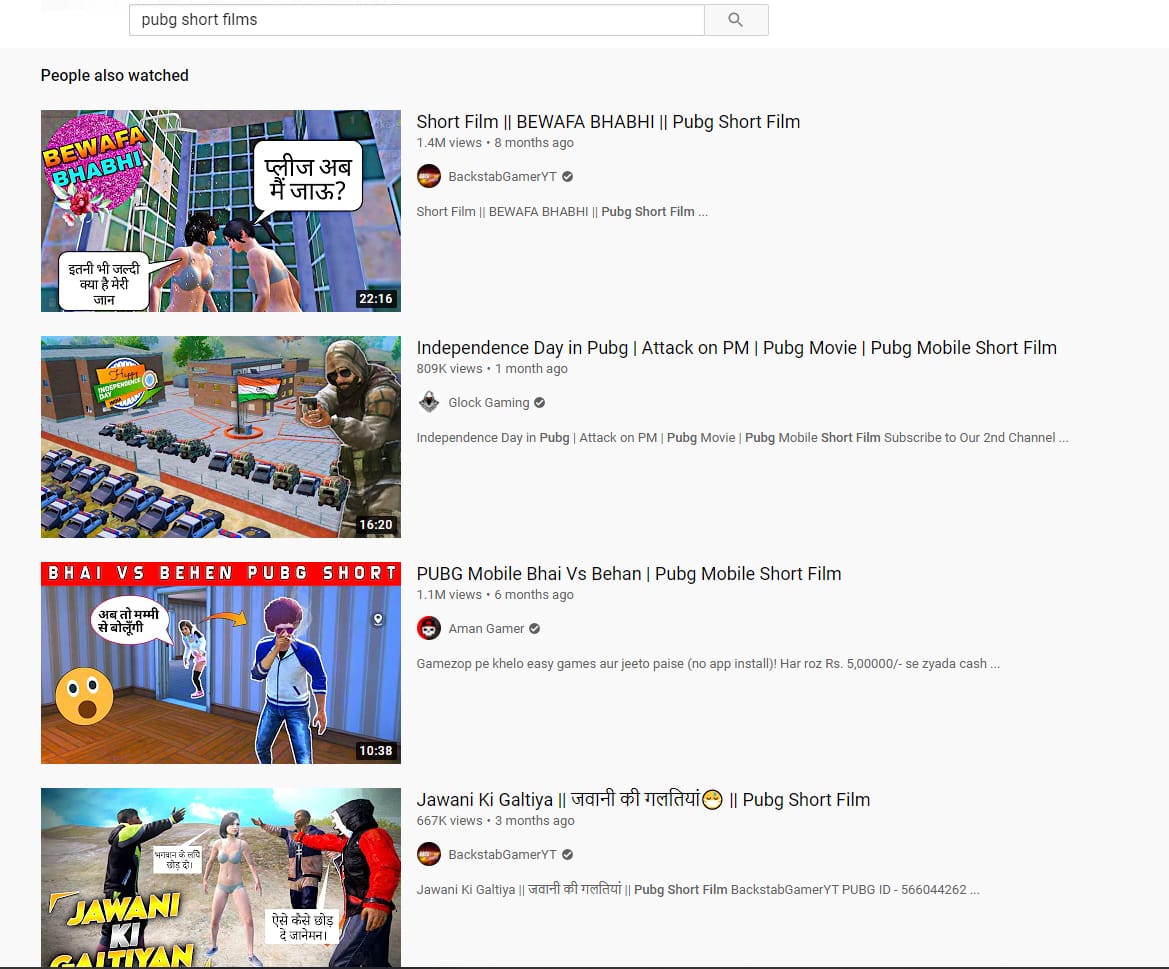

Similarly, the emotional power of PUBG for young, small-town Indians was entwined with the dream of translating “skill” into long-distance friendships and vicarious travel, while having fun with one’s peers along the way. In a reversal of the Rohitash Yadav-style “Real Life” PUBG battle videos, there are many #pubgshortfilms that appeared on Indian YouTube through the lockdown as well. In these the standard white-looking PUBG characters, speaking in Hindi, enact stories that take up such themes as Love Marriage vs. Arrange Marriage, Raksha Bandhan, and of course a whole lot of darker stuff and erotica (watch Maa Beta or Wo at your own peril).

Swap the sportsbra for a low-cut choli and the aesthetic is strangely reminiscent of the sexploitative short stories in magazines like Saras Salil and Manohar Kahaniyan. Made by creative people who can’t afford cameras, sets, actors and high production values but still want to write dialogues, these PUBG films reflect very Indian realities and fantasies.

With PUBG and TikTok gone for now, the Indian users of these platforms are mostly treating the loss as a patriotic sacrifice for the greater good. As people continue to lay down their livelihoods, links to international communities, and even local entertainment at the altar of nationalism, the idea of India seems to drift higher and higher away.

Screenshot from BackstabGamerYT’s PUBG short film “A True Story” released on YouTube for Independence Day 2020.

Screenshot from BackstabGamerYT’s PUBG short film “A True Story” released on YouTube for Independence Day 2020.